In This Article

Not long ago, we appeared to be staring into the abyss of a recession. Goldman Sachs had put the odds of a global recession in 2025 at 60%, although it has now dropped that estimate to 35%. The U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis concluded that GDP in Q1 2025 decreased 0.3%, although estimates for Q2 are positive.

Given this situation and the enormous rise in housing prices over the last 15 years, many believe we are about to see a repeat of 2008. I explained some time ago why, even if there is a recession, there will be no repeat of 2008 in the housing market. But I’ve had enough run-ins with angry commenters explaining how the real estate market is about to collapse to know this perspective isn’t universally shared.

Part of it may be that with some dark economic clouds on the horizon, there is a tendency to believe the next economic crisis will be like the last, despite it rarely working out that way, historically speaking. However, some of it may just be that enough time has passed that many of us have forgotten what exactly caused the greatest real estate meltdown in American history.

So, let’s jump back in time to revisit the absolute madness that was the housing market in the first decade of the 21st century.

“Housing Prices Always Go Up”

I started investing in real estate in 2005 (good timing, right?), and one of the first things I heard was the very odd-sounding phrase, “Housing prices always go up.” Admittedly, the phrase itself usually came with a caveat: “OK, not always, but just about.”

Still, the sentiment hovered about like the air you breathed at the time and was said or implied in a thousand different ways. Now, obviously, it wasn’t true, but more importantly, why would anyone even think this?

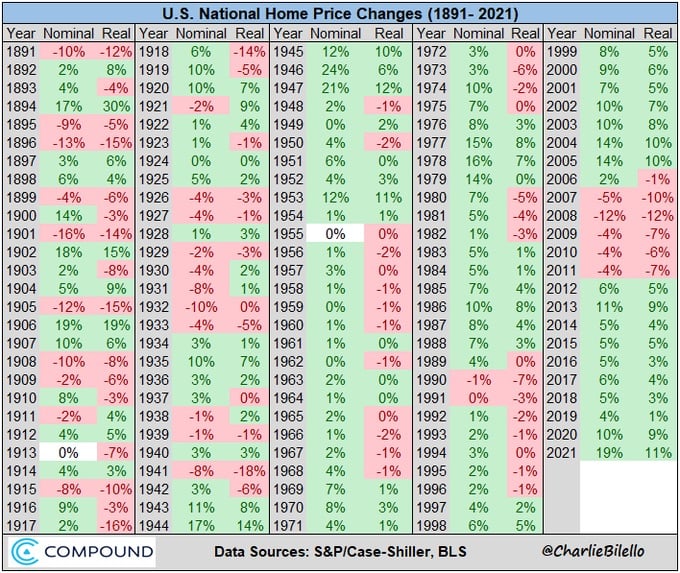

Part of the reason for this mass delusion was that there is a kernel of truth in it. On a country-wide basis, housing prices rarely go down. Indeed, if you’re on social media, you have very well seen this chart floating around:

Now, remember, this was 2005, so there were only two negative years between 1950 and then, and both of those were less than 1% negative. That sounds pretty encouraging, especially when you compare it to a similar chart for the S&P 500, which is littered with red years.

Unfortunately, while the chart is factually correct, there are many problems with it. First, it doesn’t go back far enough. Notice how the Great Depression isn’t included?

This reminds me a bit of Long Term Capital Management. The founders won a Nobel Prize in economics for their mathematical approach to arbitrage. But that math was only based on a few years of data. So when a black swan event occurred (namely, Russia’s debt default in 1998), the company collapsed in historic fashion. It was so over-leveraged that it threatened to bring down the entire global economy and ended up requiring a U.S. government bailout. (Spoilers for 2008, by the way.)

The second problem with that chart is that it only looks at nominal returns. When you go back to the turn of the century and also adjust for inflation, the chart looks quite a bit less favorable.

When you put it on a chart, the year-over-year changes look pretty modest for the most part until just before the beginning of the new millennium.

(For those wondering why I don’t believe the recent sharp uptick is near as problematic as 2008, see here.)

What really got people thinking that housing prices were immune to price corrections was the dot-com bust and the 2001 recession. GDP fell only 0.6% due to the tech stock-induced bust that caused the S&P 500 to fall 43% from peak to trough, and the Nasdaq plummeted 75%.

Real estate prices, however, were not just resilient—they were great. Housing prices went up

9.3% in 2000 and 6.7% in 2001 (and over 5% in real terms both years). Real estate became viewed as a completely safe haven in contrast to the precarious nature of the stock market. A sort of irrational exuberance formed around the housing market.

I remember talking to one seller in 2006 who said he wanted to hold the property for another year so he could sell for 10% higher, as if it was some law of nature that properties go up in value on a preset schedule.

The fundamentals underlying the housing market had truly fallen completely out of whack and came down to Earth with a horrendous thud. From peak to trough, housing prices nationwide fell 30%. The stock market did even worse, falling almost 50% and not reaching its pre-crash high again until 2012. Approximately 9 million jobs were lost, and the unemployment rate peaked at over 10%. One estimate found that household wealth declined by over $10 trillion.

In 2008, there were over 2.3 million foreclosure filings, more than triple the number in 2006. And 2009 and 2010 were both even worse, with over 2.8 million each. The number of foreclosure filings wouldn’t return to the 2006 level until 2017.

So Who Did What?

As I’m sure you can remember, there was an enormous amount of debate after the bottom fell out about whether Wall Street or the government caused the crash. But the thing is, we need to embrace the “genius of the AND.”

Wall Street and the government both did it. They both did in spades.

We’ll start by looking at the claim that deregulation caused the collapse. On this point, the answer is, sort of.

Deregulation myths

The mantra on the left was that greed had caused the crash, as if greed had just been invented sometime around the turn of the century. When pressed a bit harder, deregulation would be the stated culprit, and this is where I (partially) diverge from a lot of liberal commentators.

Deregulation did play a role, but oddly enough, the most common scapegoat for deregulation did not. That scapegoat was the Gramm–Leach–Bliley Act that was passed in 1999 and overturned part of the Glass-Steagall Act of 1932.

Glass-Steagall separated commercial banking and investment banking and prohibited any institution from engaging in both activities. Gramm-Leach-Bliley didn’t even completely undo this part; it just made it so that both types of firms could be consolidated under a single holding company.

Now, admittedly, I think there’s a very good case for separating these two types of banks. This legislation likely contributed to the major consolidation of financial institutions we’ve seen in the last few decades and helped to embed the “too big to fail” mantra. But there is little reason to think this had anything to do with the crash. As economist Raymond Natter pointed out:

“[T]hese allegations never specify the exact link between [Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act] and the crisis. The reason is that there is no readily apparent link between the two events. Simply put, the provisions of the Glass-Steagall Act that were repealed by GLBA did not prohibit the origination of subprime mortgage loans, to the securitization of mortgage loans, or to the purchase of mortgage-backed securities that resulted in the large losses that banks and other investors suffered when the housing bubble finally burst.”

Indeed, if you look at the biggest banking collapses during that crisis, none of them were acting as or holding both an investment bank or commercial bank. Lehman Brothers and Bear Stearns were exclusively investment banks, and Washington Mutual (the largest bank failure in U.S. history) was exclusively a commercial bank.

It should also be noted that Canada had no equivalent to Glass-Steagall and yet had not a single bank failure in 2008. European countries also never had any such wall separating commercial and investment banks.

That is not, however, to say that regulation (or the lack thereof) had no part to play.

The role of regulation (and deregulation) in the crash

There are three ways in which I believe the regulatory framework of the United States leading up to 2008 played a significant role in the crash. The first is where liberal economists are at least partially right. For all the ink spilled over Gramm-Leach-Bliley, the real piece of deregulation that exacerbated the crisis was the Commodity Futures Modernization Act of 2000. This law deregulated over-the-counter derivative trades like the infamous credit default swap.

Credit default swaps began in 1994 before that legislation was passed, but they really took off afterward, especially as investors who saw the crash coming—such as Michael Burry and John Paulson—bought them in droves. Credit default swaps are an absurd financial instrument where a financial institution will pay a third-party investor a stream of monthly payments unless an underlying loan goes into default, in which case the institution will pay out the security’s value to the investor.

Credit default swaps effectively act as a sort of bizarro-world insurance where the insurance company pays monthly premiums to you unless your house burns down, in which case, you have to pay the insurance company the cost to repair your home.

This increased the demand for mortgage-backed securities, but it certainly didn’t in and of itself cause the housing crisis, nor even the housing bubble to inflate as much as it did. But what it absolutely did do was dramatically exacerbate the financial carnage once the bubble started to deflate, as financial institutions had to deal with both massive losses on their loans and many also had to pay out huge lump sums on all the credit default swaps they had purchased.

AIG—which specialized in selling insurance to financial institutions and ended up requiring the biggest government bailout—was especially hammered by its exposure to credit default swaps.

The second problem with the regulatory framework was what economists refer to as moral hazard. This refers to the expectation large financial firms have that if things really go sideways, Uncle Sam will foot the bill. This expectation creates an incentive to engage in risky behavior. After all, if you went to Vegas and knew the government would pick up the tab if you lost, wouldn’t you just let it ride?

You might also like

It’s mostly forgotten today, but the 1990s saw a wave of government bailouts. First, in 1989, the U.S. government provided $50 billion to bail out failed Savings and Loans institutions. In 1995, the government provided a $50 billion bailout to Mexico to help stabilize the peso. In 1998, the government arranged the aforementioned $3.6 billion bailout of Long Term Capital Management just after it was offering bailouts to South Korea and Indonesia during the 1997 Asian Financial Crisis.

It had just become common wisdom that if your bank was big enough and you ran it into the ground, the taxpayers would pick up the tab (and you could still give yourself a nice bonus afterward for such a good day’s work).

Needless to say, such incentives didn’t help. But it got even worse when the crisis actually came, and the government acted erratically by bailing out Bear Stearns while letting Lehman Brothers fail. This left investors in the dark as to what to expect.

Lastly, the government failed to enact any regulation that might have stopped or at least blunted the impact of the housing bubble. Brooksley Born, as chair of the Commodity Futures Trading Commission, tried to regulate derivatives, but without any luck.

Beyond that, the government made no attempt to deflate what was becoming a clear bubble. The ratio of median annual income to housing prices had grown from 3.5 in 1984 to 5.1 in 2007. By itself, this might not have raised an alarm, as interest rates were much lower in 2007 than they were in 1984. But just a little digging made it easy to see just how fragile the market actually was.

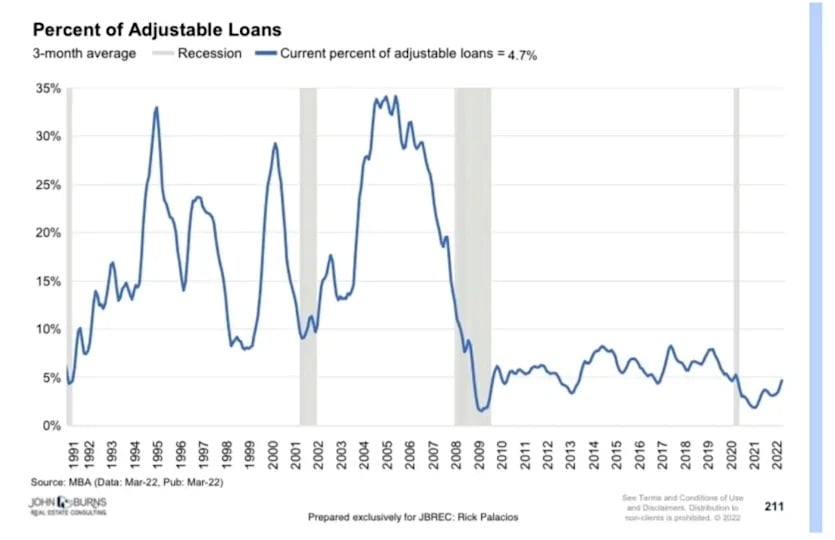

For one, almost 35% of mortgages being taken out on the eve of the crash were adjustable-rate loans, often with low-interest “teaser” rates.

Furthermore, the number of poorly qualified buyers should have been extremely disconcerting. Whereas about 75% of mortgages originated in 2022 had a credit score of 760 or more, that was less than 25% in 2007. Around 15% had credit ratings under 620.

At no point did the government make a concerted effort to rein in adjustable-rate, teaser loans, stated income approvals (the dreaded NINJA loans: No Income No Job No Assets), or anything like that. In fact, they were too busy pouring gasoline on the fire.

The government’s role in the crisis

The government’s role as watchdog for the financial markets was more a case of the fox guarding the hen house. Instead of deflating the housing bubble, the government’s actions were clearly geared toward blowing it up.

In a case of bipartisan insanity, the Democrats’ push for affordable housing and the Bush administration’s push for an “ownership society” coalesced into a ticking time bomb. Apparently, owning a home was all that mattered. Whether you could afford it was a question only Debbie Downers liked to ask.

A variety of legislative acts were passed to increase homeownership and encourage banks to lend to low-income households. The most famous of these acts was the 1977 Community Reinvestment Act, which the Clinton administration used far more aggressively than previous administrations had.

Yet this was only a small piece of the puzzle. The big problems involved the Federal Reserve and the two most famous government-sponsored entities, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. We’ll start with Fannie and Freddie.

In 1999, Steven Holmes wrote an infamous piece for The New York Times, “Fannie Mae Eases Credit to Aid Mortgage Lending.” In it, he wrote, “[T]he Fannie Mae Corporation is easing the credit requirements on loans that it will purchase from banks and other lenders.”

Holmes went on to quote then-Fannie Mae CEO Franklin Raines:

“Fannie Mae has expanded homeownership for millions of families in the 1990s by reducing down payment requirements. Yet there remain too many borrowers whose credit is just a notch below what our underwriting has required who have been relegated to paying significantly higher mortgage rates in the so-called subprime market.”

Holmes then ominously notes, “In moving, even tentatively, into this new area of lending, Fannie Mae is taking on significantly more risk.”

You think?

Fannie Mae was set up in the wake of the Great Depression to buy mortgages on the secondary market in order to expand homeownership. Freddie Mac was later created in 1970 to expand the secondary market with an added focus on serving smaller financial institutions. Combined, they support a whopping 70% of the mortgage market in the United States.

Fannie and Freddie led the charge on expanding mortgage-backed securities, with over $2 trillion in MBS in 2003 and dwarfing all private institutions until 2005. Approximately 40% of all newly issued subprime securities were purchased by either Fannie or Freddie in the run-up to the financial crisis. And these institutions generally set the tone for other market participants to follow.

Remember, that New York Times article came out in 1999. Here’s what happened to subprime in the years that followed.

Subprime adjustable-rate mortgages ended up having an astronomical delinquency rate—over 40%! On the other hand, prime fixed-rate mortgages never had a delinquency rate exceeding 5%, even at the height of the crisis.

The Federal Reserve also had a major role to play. The fact that the then-Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke could claim “the troubles in the subprime sector on the broader housing market will be limited, and we do not expect significant spillovers” in May 2007 shows, at best, they were asleep at the wheel. But the Fed’s role in the crisis is much deeper than that.

It goes back to the 2001 dot-com bust. It was at that time that economist Paul Krugman gave his infamous advice on how to get the economy back on its feet:

“To fight this recession, the Fed needs more than a snapback; it needs soaring household spending to offset moribund business investment. And to do that, as Paul McCulley of Pimco put it, Alan Greenspan needs to create a housing bubble to replace the Nasdaq bubble.”

And that’s exactly what the Fed did.

Despite the 2001 recession being quite mild, the Fed held interest rates at (what were then) historic lows. The Fed pushed the federal funds rate down from about 6.5% in 2001 to 1%, and then held it there until the middle of 2004.

Austrian economists like to talk about the “natural rate of interest,” namely, what interest rates would be if they were set by the market, given the demand for loans and the amount of savings available. Keynesian economists would argue that it’s not so simple. Regardless of that controversy, there is certainly a natural range of interest. And given the strong rebound from the 2001 recession (i.e., high demand) and abysmal savings rate at the time (i.e., low supply), the price of money should have been significantly higher than it was.

(On a side note, when loans go into default, money is literally taken out of existence, which is a major reason that, despite very low interest rates after the crisis, inflation was low and, at least for a while, asset prices didn’t skyrocket.)

At the beginning of this article, I noted how real estate prices increased by over 5% in real terms in 2001. This is why. The Fed’s excessively low rates inflated housing prices, creating a false sense that real estate always went up.

And given both the government’s behavior and Wall Street’s behavior, that excess liquidity made its way into blowing up the real estate bubble (both before and after the bubble burst in different ways).

Wall Street’s role in the crisis

I am generally in favor of a free market, but I do find it a bit odd the way many defenders of capitalism blamed it all on the government in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis. It was as if poor Goldman Sachs and the downtrodden Countrywide just had to make a bunch of farcically complex derivatives because the government was pushing banks to lend more and more to less and less-qualified borrowers.

We should remember that 60% of subprime mortgages did not go to Fannie and Freddie. These were issued by commercial banks themselves. And then those terrible loans were securitized into obscure financial instruments that hid their underlying risk and sold all over the world, as will be discussed shortly.

No, Wall Street’s behavior before the crash was atrocious. Although it wasn’t just Wall Street, unfortunately. The problems were systemic.

For one, there was a disastrous disconnect between those issuing loans and those buying them. Mortgage originators got paid for issuing loans. Once they were issued, the issuer would sell the mortgage and move on to the next borrower. The incentives were all backwards.

And as one might expect, such terrible incentives laid the groundwork for rampant fraud. A paper by John M. Griffin on the role of fraud in the crisis is worth quoting at length:

“Underwriting banks facilitated wide-scale mortgage fraud by knowingly misreporting key loan characteristics underlying mortgage-backed securities (MBS). Under the cover of complexity, credit rating agencies catered to investment banks by issuing increasingly inflated ratings on both RMBS and collateralized debt obligations (CDOs). Originators who engaged in mortgage fraud gained market share, as did CDO managers who catered to underwriters by accepting the lowest-quality MBS collateral. Appraisal targeting and inflated appraisals were the norm.”

The collateralized debt obligations mentioned by Griffin were packages of mortgages that Wall Street firms often sliced and diced in a way to obscure the underlying risk. These instruments offered the illusion of diversification. But given that, at least for the lower tranches of such CDOs, that diversification amounted to nothing more than a diverse array of garbage, it didn’t offer much security.

In the end, as Niall Ferguson concluded, “The sellers of structured products boasted that securitisation allocated assets to those best able to bear it, but it turned out to be to those least able to understand it.”

The crisis was globalized by this manner of securitizing garbage and selling it off to the unsuspecting. (Although, while the global crisis started in the United States, many other countries had housing bubbles as well.)

Lastly, there were the rating agencies that consistently put their triple-A stamp of approval on farcically complex securities, backed by subprime, teaser-rate NINJA mortgages right up until the whole house of cards collapsed. The biggest problem with these agencies was pretty simple: They are “issuer-paid,” which created an enormous conflict of interest.

The proper role of financial institutions is to effectively distribute capital in a manner that allows entrepreneurs to expand their businesses and consumers to purchase homes and other expensive assets they can afford, and to do so in a way that grows the economy while mitigating risk. What actually happened, however, was that throughout the run-up to the collapse, Wall Street did virtually nothing to ameliorate risk, and instead engaged in extremely risky, highly leveraged, and overly complex behavior to maximize profits in the most myopic and shortsighted way possible. The results shouldn’t have been surprising.

They certainly deserved no pity, nor our tax dollars (although that’s another story).

Final Thoughts

The 2008 financial crisis was easily the biggest economic disaster of my lifetime and has had lasting effects on the real estate industry, as well as the economy as a whole. Indeed, it’s had an enormous effect on our collective psyche, particularly for those of us in real estate. In a variation of Godwin’s Law, the longer a conversation about real estate goes, the likelihood of the 2008 real estate crash being brought up approaches one.

Lately, many have been warning that we are facing a second such crash. Again, that is highly unlikely. The fundamentals of real estate are far sounder now than then. Financial crises and recessions rarely play out the same way twice in a row.

In 1929, it was an overvalued stock market and a foolhardy attempt to return to the gold standard at pre-World War I prices. In the ‘70s, it was an oil shock and the inflationary consequences of “guns and butter”; in 2001, it was the dot-com bust; in 2008, it was housing; and let us not forget, in 2020, a pandemic.

Next time around, given the way things are going, it very well might be a sovereign debt crisis. Hopefully not. But either way, it’s still critical to understand how such a disaster came about to avoid it from happening again, and also so as not to assume a run-up in prices necessarily means it’s happening again.

Analyze Deals in Seconds

No more spreadsheets. BiggerDeals shows you nationwide listings with built-in cash flow, cap rate, and return metrics—so you can spot deals that pencil out in seconds.